Both mindfulness and creativity have recently come to the frontline of educational and therapeutic interest, despite their relationship not yet being extensively investigated. This article reflects on the connection between these topics with the aim to understand exactly where and how they are related and how they can complement each other. My goal is to reflect upon the findings from the literature and from my own practice as artist, psychologist, Vipassana practitioner and Zentangle teacher to consider the implications for educational practice and therapy. My main concern is to find out how mindfulness can be applied in creative processes and how it can support learners’ creativity and their general wellbeing.

The English word mindfulness derives from the Pali term sati, found in the early Buddhist teachings and Tibetan meditation techniques. In this tradition, mindfulness is not just mental training but a part of an all-embracing ethical program to foster wise action, social harmony, and compassion. Owing to Vipassana meditation, which has been taught since the 1970s in Western Europe, the term mindfulness has become gradually more popular in Western culture. Due to its beneficial effects, such as improved emotional regulation, concentration, and interpersonal skills, the mindfulness training – stripped of its religious or ethical contexts – has been integrated in different therapeutic settings such as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction by Jon Kabatt Zinn (1979), Dialectic Behavioral Therapy by Marsha Linehan (1980s) or Mindfulness Based Art Therapy founded by Laury Rappaport (2009).

Mindfulness is generally defined as a state of nonjudgmental, moment-to-moment awareness of feelings, thoughts, and bodily sensations that may arise. Although it is a basic human ability that we all share, reaching this mental state initially requires more effort. This skill can be developed and improved through regular meditation.

Two of the main techniques used in Vipassana and discussed frequently in the literature on mindfulness include open-monitoring meditation and focused-attention meditation. Open-monitoring meditation is the practice of non-judgmental observation and attendance to sensations or thoughts, while refraining from focusing on specific tasks or ideas. Focused-attention meditation, on the other hand, develops the ability to concentrate attention and awareness on a particular aspect, such as breathing. This kind of meditation is aimed at reducing mind-wandering, as attention is gently yet consistently directed back to the object of attention, whenever it begins to drift.

Both meditation techniques have been shown to have a positive influence on emotional regulation, body awareness and concentration (e.g. Shin-Ling King at all. 2013) and are frequently used in therapies and education. This has resulted in a recent drive to investigate the influence of mindfulness on creativity, defined as the ability to make or otherwise bring into existence something new, whether a new solution to a problem, a new method or device, or a new artistic object or form.

My research of the literature revealed two different approaches to this subject. On the one hand, there are efforts to practice mindfulness prior to the creative task with the aim of enhancing the creative performance. Other approaches directly integrate the elements of mindfulness into creative activities. Here the creative mindfulness practice seems to be a substitute for mental training and the aim is not just to enhance the creativity but also to reduce stress and improve general wellbeing through the power of art.

Regarding the former approach, one of the most well-known studies from 2012 by Lorenza Colzato and Dominique Lippelt has shown that mindfulness can influence creativity differently, depending on the kind of meditation involved. While open-monitoring meditation may increase creative-divergent thinking, it seems that focused-attention meditation may be either unrelated to creativity, or in certain instances may even impede creativity in problem-solving scenarios. For educators interested in enhancing creativity, this leaves questions regarding the type of meditation to use with students prior to creative tasks.

As for the latter approach, we can find therapeutic approaches, such as MBAT as well as creative methods that were not originally invented for therapeutic purposes but are increasingly being used in healthcare due to their positive effects. One of most popular of these methods is Zentangle founded in 2004 by Rick Roberts and Maria Thomas.

As a recently certified Certified Zentangle Teacher I am particularly interested in examining which elements of mindfulness practice can be implemented through the Zentangle method and how they affect participants’ creativity and wellbeing.

Psychologist Matthijs Baas confirmed the findings of Colzato and Lippelt in his research in 2014 on mindfulness and creativity. Furthermore, his findings suggest that mindfulness has various key elements and skills, the most important of which are:

- observation (the ability to observe internal phenomena and external stimuli);

- acting with awareness (engaging in activities with undivided attention);

- description (the ability to describe phenomena without analyzing conceptually);

- accepting without judgment (being non-evaluative).

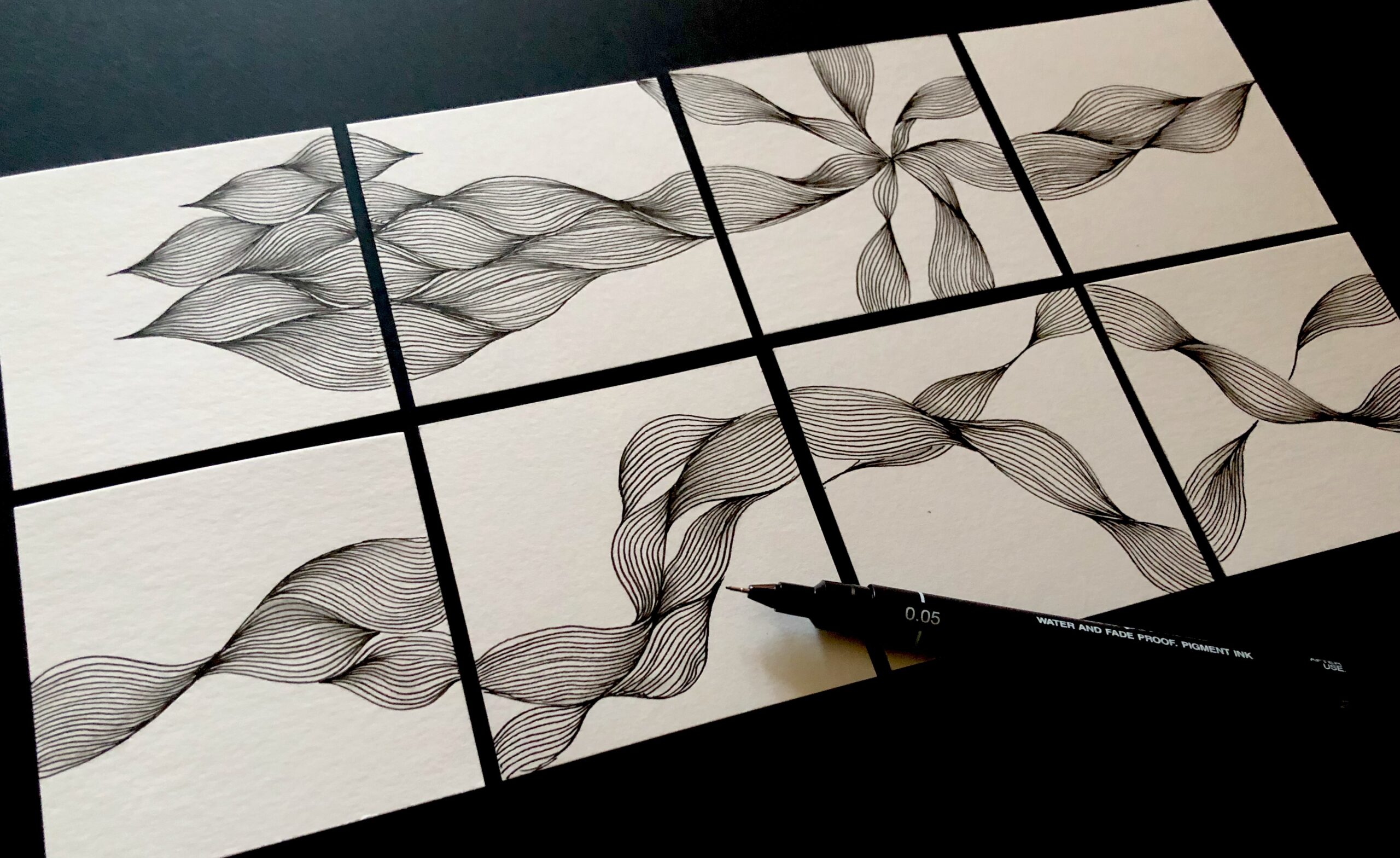

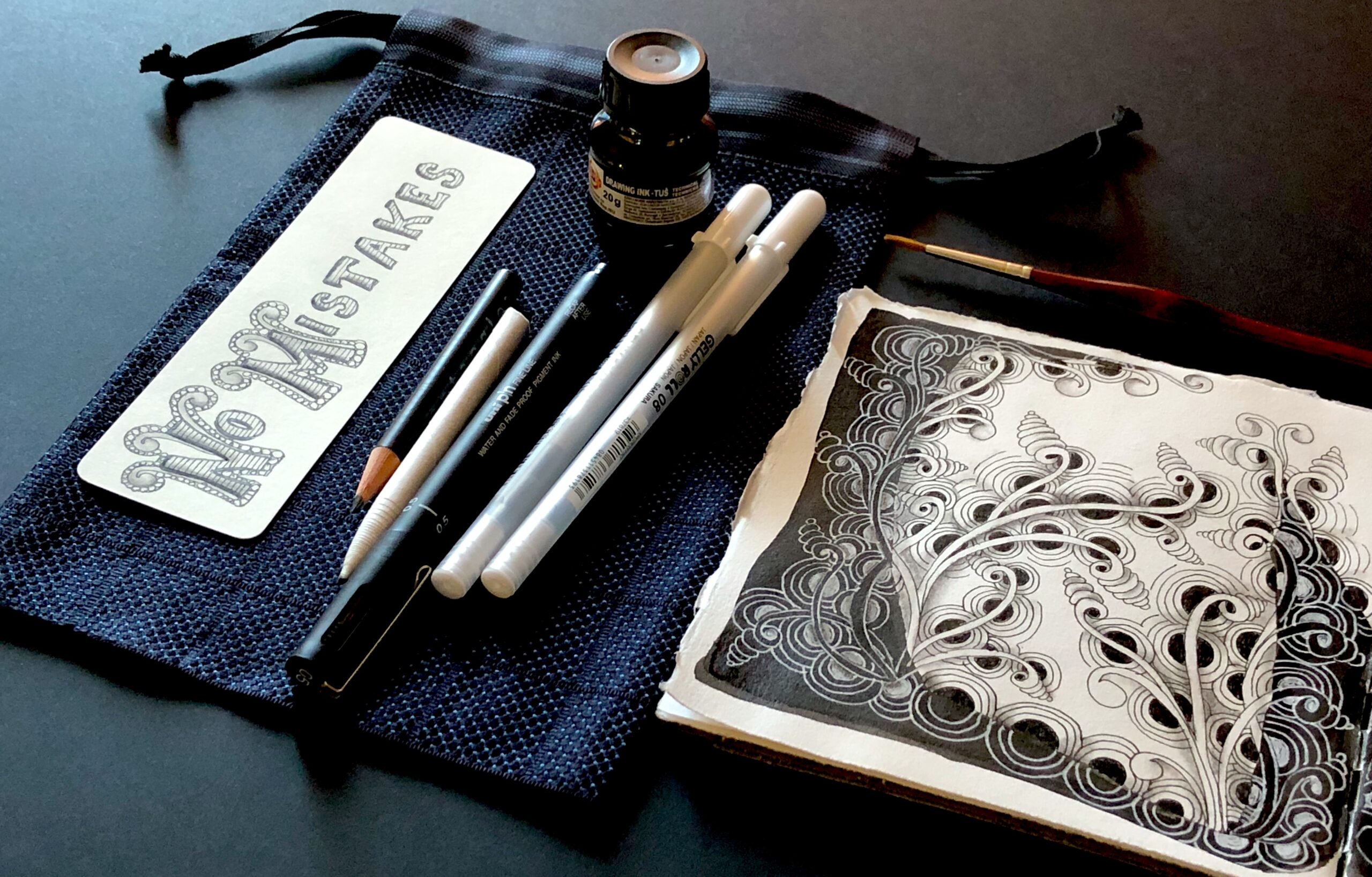

According to my observations and experience of Zentangle work with clients, it seems to me that at least three of these elements are well represented during sessions guided by a trained teacher. Firstly, Zentangle usually starts with a short meditation, which invites participants to observe their breathing, body sensations and conditions. After this introduction the attention is guided towards the precious materials: different papers, pens and pencils. A moment of gratitude then proceeds the first action. The participants are asked to consciously perceive the visual and haptical sensations produced by specific tools at the beginning as well as during the session. Secondly, the constant focus on the act of drawing requires acting with awareness. The simple elements such as lines, circles and dots are repeated purposefully with slow movements to create a complex ornament. The patterns themselves are deconstructed into step-by-step instructions, which are easy to follow if approached carefully. This clearly structured process may work similarly to focused-attention meditation. Furthermore, the sensation of drawing on high-quality paper increases sensory pleasure, which in turn supports anchoring attention in the present moment. The focus of attention on visual elements helps to prevent mind wandering and rumination, a psychological habit of dwelling on stressful thoughts concerning the past or future.

Finally, the element of accepting without judgement is the core of Zentangle method, represented in the philosophy of “no right or wrong” regarding dealing with mistakes. According to this philosophy, mistakes are not allowed to be erased – instead they are accepted as a possibility to create something unexpected. The students are encouraged to discover, explore, and embrace their imperfections and individual styles. Although each student follows the same basic Zentangle instructions, their resulting artworks will always be unique. The individual artist in each student and teacher is encouraged and given opportunities for expression.

The no mistakes philosophy may at first seem contractionary to the specified pattern structures. There are argued to be different brain regions involved in the process of following structures as opposed to using unexpected errors as a chance for creativity, which requires a certain degree of mind-wandering and openness to random insights. Zentangle seems to involve both elements of meditation practice – focused and open monitoring. Thus, it embraces both aspects of creation: convergent and divergent thinking. Convergent thinking is helpful in learning, analyzing, accurately following structures and accomplishing tasks; whereas divergent thinking is central to finding new solutions.

According to the first scientific research on the effects of Zentangle conducted and coordinated by the Zentangle Foundation, the method has similar effects to mindfulness meditation and can reduce stress, rumination and even the sensation of physical pain. There is still a strong need for more randomized controlled studies, more methodological rigor and for the use of larger sample-sizes. Regardless, the incredible popularity of the method all over the world demonstrates the effectiveness of movement-based creative work. The success of movement-based creative work can be attributed to shifting conscious awareness to the body and focusing on a simple action. This action and its result – the stroke of a pen or graphite on the paper resulting in a beautiful pattern arrangement – offers an easier and more rewarding anchor to our attention than the breathing exercises of focused-attention meditation, especially when distance can be created from emotionally loaded thoughts. Once the overactive mind finds calmness in creative tasks the more challenging traditional mindfulness training can be offered.

Here you can find other articles about Zentangle:

«Landschaft hervorbringen – mit Zentangle Art»

Certified Zentangle Teacher, Beata Sievi